Olivier Walther, University of Florida

17 October 2024

Twenty years after Alpha Oumar Konaré’s call for pays-frontières, cross-border co-operation in West Africa is under threat. By militarising border regions and transforming them into safe havens, states and Jihadist groups have contributed to destroy their most obvious social and economic manifestations.

More violence in borderlands

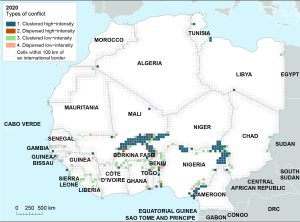

The insurgencies that have emerged in West Africa over the past fifteen years show a clear tendency to concentrate close to borders. Violence is particularly intense and clustered along the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger borders and in the Lake Chad Basin (Map 1), two regions that before the mid-2010s were recognised as having the greatest potential for cross-border co-operation.

For decades, organisations such as the Liptako Gourma Integrated Development Authority (LGA), the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), and a myriad of local initiatives had attempted to manage human and natural resources while building stronger institutions in these regions. Why, then, has political violence found its most extreme manifestations in areas where cross-border co-operation was so developed?

Map 1. Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator (SCDi) in border regions, 2020

The West African roots of cross-border co-operation

The least convincing answer to this question is that cross-border co-operation is a concept imposed by African regional organisations, with the support of international donors. In the current context of rejection of the West, some will note that the model of cross-border co-operation applied in West Africa shared many similarities with that of the European Union. In both regions, priority was given to institution-building rather than support for economic activities, as is more common in the Anglo-Saxon model.

However, blaming the model of cross-border co-operation used in West Africa overlooks the fact that its origins were firmly rooted in West African thinking. It was, in fact, the concept of pays-frontière developed by former Malian President Alpha Oumar Konaré that emphasised the importance of building local communities beyond nation-states in the early 2000s. For Konaré, a pays-frontière was “a geographical space straddling the dividing lines of two or more neighbouring states, where populations linked by socio-economic or cultural relationships live.”

This powerful idea resonated with many West Africans, whose social and economic networks are often constrained by territorial divisions, forcing them to pay a high price for the opportunity to travel or conduct business internationally. As a result, the African Union and regional organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) built on Konaré’s pays-frontière to help local communities overcome the obstacles created by colonial partition. For these organisations, developing cross-border infrastructure (Figure 1) and strengthening the role of local institutions were seen as ways to restore the economic centrality of border regions.

Figure 1. One Stop Border Post in Malanville, Benin

When militarisation replaces co-operation

Since independence, the lack of a productive social contract between the central government and border communities has often led to the marginalisation of border regions. Despite their strategic importance, border regions have remained under-equipped, especially towns and markets, which play an essential role in regional trade.

In these regions, most state initiatives over the past two decades have focused on strengthening security rather than rehabilitating border markets, facilitating social exchanges, or building transport infrastructure.

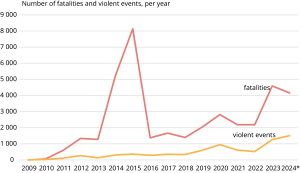

In the early 2010s, the countries bordering Lake Chad reactivated their Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to combat Boko Haram and its splinter group, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). However, this militarisation of borderlands has yielded very limited results in terms of regional co-ordination and has led to a massive increase in civilian casualties (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fatalities and violent events involving Boko Haram and ISWAP, 2009-2024

Calculations by the author. Violent events include battles, remote violence and explosions, and violence against civilians. 2024 data are projections based on a doubling of the number of events and fatalities recorded through 30 June.

In the Central Sahel, too, security aspects have largely taken precedence over support for border communities. The military coups in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have further reinforced this trend, with the creation of a joint force by the countries of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES).

Jihadism and cross-border communities

From the jihadists’ perspective, border regions represent a sanctuary that can be exploited to find new recruits, exploit agricultural and pastoral resources, or expand into new territories. The model imposed by jihadists in these regions is vastly different from both the clientelistic model of the state and the co-operative model of regional organisations. While cross-border co-operation was built on the idea that local communities should develop beyond borders, the jihadists promote exclusive religious affiliation and pit local communities against each other.

More importantly for cross-border co-operation, the Jihadist model calls into question the very existence of modern borders, which are seen as a manifestation of the failure of secular states to reconcile politics and religion. Instead of fostering a cross-border territorial community, jihadists aim to establish a transnational community of believers, which is not necessarily linked by ethnic or community ties but united by a fundamentalist interpretation of religion.

The future of a generous idea

Fifteen years after the outbreak of the Boko Haram insurgency, border communities are bearing the full brunt of joint violence by armed groups and government forces in the Sahel. This dual assault on the peripheries of the state explains why violence is particularly intense where it could have been alleviated through cross-border co-operation.

The Sahelian trend, which favours military action to the detriment of cross-border co-operation and development in general, cannot serve as a model for other states in the region. As jihadist violence spreads towards the Gulf of Guinea, cross-border co-operation is more important than ever. Konaré’s vision that the destiny of the people of West Africa is to transcend their divisions, remains the most enduring safeguard against religious extremism.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks Marie Trémolières and Sibiri Jean Zoundi for their comments on an earlier version of the draft. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author.